22.33 is an audio podcast produced by the Collaboratory in the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA).

The podcast features first-person narratives and anecdotes from people who have been involved with ECA exchange programs. The first season launched on January 2019.

Each week, 22.33 brings you tales of people finding their way in new surroundings. With a combination of survival, empathy, and humor, ECA’s innovative podcast series delivers unforgettable travel stories from people whose lives were changed by international exchange.

New episodes are released every Friday, along with regular bonus episodes. You can listen to 22.33 right here on our website or you can subscribe using any one of these podcasting apps: iTunes, Google, Spotify, Acast, Anchor, Blubrry, Breaker, Bullhorn, Castbox, Castro, Himalaya, iHeartRadio, Listen Notes, Luminary, myTuner Radio, Overcast, OwlTail, Player FM, Pocket Casts, PodBean, Podcast Gang, Podchaser, Podnews, Podparadise, Podtail, Podyssey, RadioPublic, Soundcloud, Spreaker, Stitcher, TuneIn, and YouTube. You can also subscribe via email updates.

Follow and tag us on social media using the hashtag #2233stories.

Final Episode

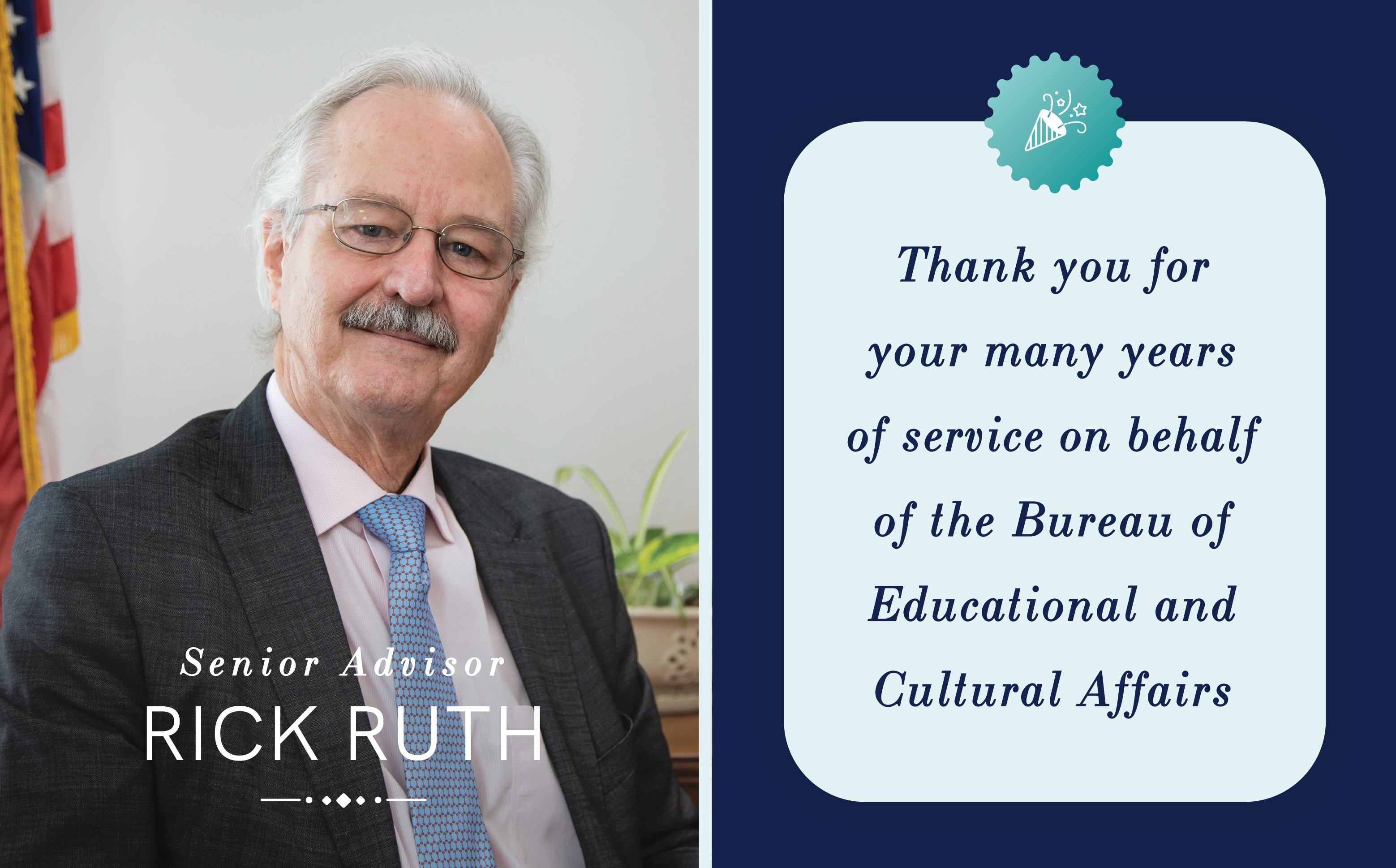

Welcome to the final episode of 22.33. In this special goodbye episode, we shifted our focus to interview Christopher Wurst, 22.33 mastermind and former director of the Collaboratory in ECA. This past summer we got to learn more about Chris, his time in ECA, and his work as a Foreign Service Officer. Thank you to everyone who has been with us on this journey. We loved being able to share two seasons of stories with you.

To keep hearing stories like the ones we shared on 22.33, head over to ECA’s new podcast series, Voices of Exchange. Use the link to subscribe today: https://voices-of-exchange.captivate.fm/listen.

TRANSCRIPT

Asha Beh:

Hello, I'm Asha Beh from ECA. Stay tuned after this episode for a special announcement on a new podcast series coming soon.

Welcome to our final episode of 22.33, for this special goodbye episode. We shifted focus to interview the host and former director of the Collaboratory, Christopher Wurst. This past summer, we got to learn more about Chris as a Foreign Service Officer and his time in ECA. So for one last time, take it away Chris.

Chris Wurst:

I grew up in a northern suburb of the twin cities that was just sort of north enough that it wasn't cool anymore. I was like the center of the not cool northern suburbs. And I credit that for my love of travel because I wanted to get away so bad because everything was the same. In a very abstract way, I would say that learning more about other countries and learning more about other people we learned that we have more in common than we have differences. And so the more we know about other people, the more peaceful we can be, the more we can learn, the more we can progress. The goal of a public diplomacy officer is to strengthen mutual understanding in the country that you are in. It's to make sure that American foreign policy is understood and communicated clearly across that country. And it is to create programs that create opportunities so that your colleagues can go forward with their work.

So a lot of mutual understanding or goodwill kinds of programs, open doors for ambassadors to have deeper relationships with their counterparts or with important people in those countries. And so it's finding unique ways in every country to create goodwill. And that goodwill helps to push American foreign policy. A Foreign Service Officer works for the State Department and we have embassies or consulates in almost every country around the world. I came into the Foreign Service so green, I had never been in a U.S. embassy in my life until I showed up for work at my first U.S. embassy. Um, I had no, I- I was so intimidated by all of these people because I didn't know. I- I, you know, I knew what they did was important, but I didn't quite have the whole picture. I was coming at it from more of a cultural affairs side of things.

Then I went to Chennai, India, and what did they call it? It was like a close and lock consulate. So we didn't have 24 hour marines at the end of the day, the last person out of the building locked up. And so there was always a duty officer who had the phone over the weekend. And I was the duty officer, um, when the tsunami happened. And the guards called and they said, “Sir, there's been a little bit of water inland, but, um, but everything's okay.” And then the, the Op-Center called me, and they said like, “This is Washington, D.C. This is the Op-Center can you tell me what's going on?” And I said, “There's been a little water inland, but everything's okay.” (laughs). They're like, turn on CNN. And so it was, um, the rest of my work from that time on was really colored by that tragedy.

And then that was the same year that there was a devastating earthquake in

Kashmir and a lot of villages up on top of the mountains were really- really rocked and people were, many people were killed and they had no way of getting supplies to them. The U.S. military and State Department and USAID, really, that was the kind of the first time that they coordinated to really help save people's lives. If it wasn't for public diplomacy, I never would have stayed in the, in the foreign service because I'm through and through an education and culture person, which is why ECA is such a- a good fit for me, because I feel so strongly about those things. Um, the Collaboratory is a place where open-minded collegial, friendly, curious people come together. And as the director of the Collaboratory for three years, I am most proud of those qualities and those attributes having stayed the same. That we are curious that we are helpful, that we are kind, that we are looking to do things that people haven't tried before, which is not always easy, and we're doing it in a space that's difficult because it is a big bureaucracy.

I waited until I had an episode that I knew was just a winning proposition. By the time we had something, I thought this is one that I- I just couldn't imagine anybody saying like, no, this is, we're not doing this. And it was the three Saudi Arabian soccer player/coaches that came through. And I felt really strongly about the way I put it together. I thought the music was really emotive in that one. And we ended up having a really candid conversation. We laughed and there was tears and it was, it turned out great. And we never looked back. There is such an embarrassment of riches in ECA when it comes to powerful and unique stories that we have only scratched the surface and that there are new and different ways that I don't even know to find those stories and to present those stories.

And I think that you have so many opportunities that you will only be limited by your own limitations. So the sky's the limit. I think my proudest moment of all of this is just the ability to consistently get people to trust me and to give me their stories. That's the most meaningful thing. And that's the thing where you go home at night and you're like, this is why I do what I do. And this is why these programs matter. And these programs actually change people's lives and they make the world a better place. And if you can say that, like, you're, that's good. I think some of the most challenging interviews where- where people were talking about really difficult things. And I had to guide them through those difficult things, where I needed to have them tell those hard stories, but it was really, uh, there was pain there, like knowing what I know now, I wish I could interview them again.

Why, um, we have talked to so many amazing people and they especially, you know, I think of the people from other countries that we've talked to cause they've gone back to their countries and the young people who are working in civil society and really making a difference. And then there are people that I will just cheer for, cheer for, from afar, like Bernadette Cell and in Hungary, who's just like giving them hell every day and hungry and just, you know, also putting herself in harm's way or Sophia Wang, you know, who's in China fighting for women's rights and- and fighting against, and- and, uh, Claire from Cameroon who, you know, who is fighting the, these fights about human rights that are really, really important, but put themselves in danger sometimes. And I'll- I'll, so I’ll always be rooting for those people. We talked to the chief justice of the Ethiopian Supreme court, the first female, chief justice.

And then we talked to high school kids. They're all inspiring. You just have to find that inspiration in those stories. But a lot of the young people that I talked to were really inspiring for me as well. I always said that the more people worked with us, the more people wanted to work with us. And I think that's the trajectory that we're on, that people like working with us. And that is proved I think because so many people do reach out to us and so many people wanna work with us. So I am optimistic in general when I see these acts of creativity and kindness in the world. And so I think we're living through a really difficult time right now, obviously, you know, we've got a global pandemic and we've got riots in the streets of the United States, and it's a massive disruption, but I believe that in disruption, you can find improvements and you can find ways forward that you haven't gone before.

And I would like to believe that in this time of disruption, we can find energy and creative ways to go forward and improve what needs to be improved. But that's not to say that we- we can't be alarmed and troubled by the difficulties of the challenges that we face. And so I actually take it as a outgoing public affairs officer, um, to Dublin as a challenge, but also an opportunity to- to take our own weaknesses and take our own flaws and find common ground and mutual understanding to go forward using that as energy. I think as a public affairs officer, I've always believed that you need to be honest about the United States, uh, warts and all as Edward Moreau says.

You have to be honest about the bad things as you're talking about the good things. When I see people out in the streets in Minneapolis, my hometown, um, doing great things, um, creating art, creating community awareness, um, building things, rebuilding things, fixing things, coming together. It's really inspiring to me. And as a former public school teacher, uh, who watches, monitors, my former Minneapolis students on Facebook, um, nothing makes me more proud than to see these folks out in the streets, doing what they can to be positive and to make the world a better place.

Asha Beh:

We want to thank Christopher Wurst for everything that he did, for 22.33 and the Collaboratory. We wish him nothing but the best moving forward. And if you didn't get the chance to listen to all of our episodes, go back and check them out. That's a wrap for 22.33. Thank you for listening. We have really appreciated it.

People, places, and international exchange.

Voices of Exchange delivers unforgettable, first person stories from people transformed by international exchange. These exchange alumni share stories of growth, unexpected friendship, and career inspiration from all around the world. This podcast is brought to you by the office of Alumni Affairs at the United States department of state. More specifically, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, also known as ECA for short. ECA is the home of people who bring you hundreds of exchange programs around the world. And yes, this podcast.

Voices of Exchange carries on the spirit of the 22.33 podcast that was also produced by ECA. Tune in March 31st, 2021, for the worldwide debut of Voices of Exchange. For the latest, follow us on Instagram @voicesofexchange or visit our website at alumni.state.gov. New episodes of Voices of Exchange will be released every two weeks on all major podcast platforms.

Season 02, Episode 51 - Trekking in India - Kiley Adams

LISTEN HERE - Episode 51

DESCRIPTION

This week, imagine you've left your comfort zone and moved to a foreign country that's 12 time zones away. There, most people speak a different language and the lifestyle and culture are radically different, but you slowly find your way.

One day you meet a group of strangers that you identify immediately as your kind of people, but just as you feel you have made it, an unspeakable tragedy occurs. How you react will change your life forever.

On this episode of 22.33, join us on a journey from Mount Rainier in Washington State to the Western Ghats in India, with a Fulbright Narrow Research Fellow studying community-based rehabilitation in rural communities.

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Wurst:

Imagine, you've left your comfort zone, moved to a foreign country that's 12 time zones away, most people speak a different language, the lifestyle and culture is radically different, but you slowly make your way. And one day you meet a group of strangers that you identify immediately as your kind of people. But, just as you feel you have made it, an unspeakable tragedy occurs. How you react will change your life forever. You're listening to 22.33, a podcast of exchange stories.

Kylie Adams:

In the first one I showed up to, there's women wearing saris. And I'm like, we're going hiking. I'm there in my hiking boots and my hiking pants, all this fancy gear I had brought. Some people were wearing slippers is what they call sandals. They were wearing their slippers still. And it was the first time I felt like I absolutely had found my people in India. I had this community. We were trekking. We were sleeping under tarps during monsoon season.

Chris Wurst:

This week, finding one's people, hiking in slippers, and turning tragedy into a lifetime of service. On this episode, a journey from Mount Rainier, Washington to the Western Ghats in India and finding one's calling along the way. It's 22.33.

Intro Segment:

(Music)

We operate under a presidential mandate, which says that we report what happens in the United States, warts and all.

These exchanges shaped who I am.

And, when you get to know these people, they're not quite like you. You read about them. They are people, very much like ourselves. And it is possible to create...

(Music)

Kylie Adams:

My name is Kylie Adams. I am from Edgewood, Washington, which is right at the base of Mount Rainier in the Cascade Region of Washington State. I went to the University of Notre Dame. I studied biological sciences. I was on the Fulbright Student Research Program, specifically the Fulbright Narrow Research Fellowship. And I was studying community-based rehabilitation for treating people with disabilities in rural communities.

Kylie Adams:

I lived in Southern India. I was based out of Chennai, India. But, because my research was in rural communities, I got to travel all throughout both Southern India and then all the way up in the Northeast bordering Tibet and Myanmar. I lived in a place called [inaudible 00:03:21] as well.

Kylie Adams:

I knew, going to India, that one of the hardest parts of me going was that I wouldn't have my mountain in my backyard. I'm very influenced by growing up near and around mountains. And I knew I wanted to get involved in the hiking and trekking culture of India. And, in Chennai, when I first got there and it's this concrete jungle, I was afraid that I wouldn't have that opportunity.

Kylie Adams:

But I immediately found out about this group called the Chennai Trekking Club and reached out to them. And they had organized all these hikes in a mountain region called the Western Ghats and some other hill stations to our North. And I got on their email list and I found out they had a women's trekking group that was for all women, mostly for women that hadn't done a lot of trekking before. And I reached out and said, oh, I have a lot of experience trekking. Is this still something I can go on? And they said, absolutely. We would love to have people help lead these treks, encourage other women, show them that it's okay to go out in the outdoors, go for overnight treks.

Kylie Adams:

And the first one I showed up to, there's women wearing saris. And I'm like, we're going hiking. I'm there in my hiking boots and my hiking pants, all this fancy gear I had brought. Some people were wearing slippers is what they call sandals. They were wearing their slippers still. And it was the first time I felt like I absolutely had found my people in India. I had this community. We were trekking. We were sleeping under tarps during monsoon season. And they really were my first home in India.

Kylie Adams:

Flash forward a few months, I've gone on several hikes with these people. I call several of them my family. We eat, and swim, and have a great time together. And this will seem like it's not connecting at first, but I was given the opportunity to give a TED Talk in India. And I gave the TED Talk and afterwards my phone had just blown up and I thought people were congratulating me for giving a TED Talk. And it actually was a bunch of people in the trekking community reaching out to me asking if I was okay. And I was really concerned why these people were messaging me.

Kylie Adams:

And I actually found out that there was a very tragic fire that killed about 14 of my best friends in the trekking group that had been hiking that same day on a trek that I was actually supposed to lead, a women's only track celebrating Women's Day. And I had thought, when I finished this TED Talk, it would be this great moment of celebration, but I was really sitting with this idea that probably the most influential part of my experience in India to date had been my time spent in the hills talking and walking with, especially these other women. And I had a really hard time coping with that. And I didn't even want to stay in Chennai. Who do I ask to go to dinner anymore? I've lost all these close friends.

Kylie Adams:

I started thinking of other ways I could get involved with communities that in India don't always have access to the outdoors, be it women of Chennai that might not be encouraged to go explore. And I realized that, I mean, my research being in disability work and working with people with disabilities, that that's a community that also doesn't often get equal access to the outdoors, be it because trails are not accessible to people who are blind, or visually impaired, or you're just discouraged from a cultural framework of you can't do that and sort of having your bodies be defined by your disability instead of your abilities.

Kylie Adams:

And so, I reached out to an organization that I had seen called Adventures Beyond Barriers. It was a group in Pune, which is more in Western India. And they do adventure sports. They do paragliding, and scuba diving, and trekking, and mountaineering for people with disabilities. And I reached out to them and sort of explained that I was a researcher in India for a year. And I would love just to visit their programs, see what I could or couldn't help with, how I could get involved. And they responded within an hour, which is crazy, with so much excitement. And that immediately brought up my spirits, not only from this fire incident that happened, but also I just knew that this was something I wanted to focus on all of a sudden was how people that don't always have equal access to the outdoors can gain that.

Kylie Adams:

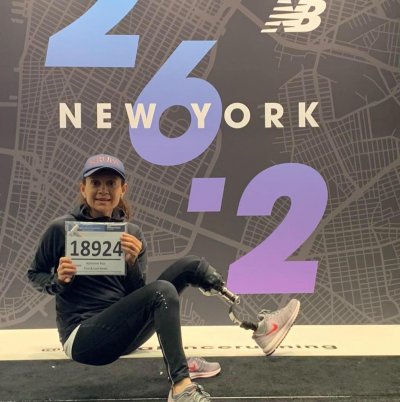

And so, I moved up to Pune for a few weeks and worked with the most amazing organization. While I was there, we actually did a trekking and rappelling, which is like reverse rock climbing, going down the mountain. We did a tracking and rappelling event for a group of people that use prosthetic limbs, a group of about 15 prosthetic users, which was the most fun. Probably my single best experience in India was that event. And I realized that I wouldn't have had that experience had it not been for I'm losing my friends in the fire and having that starting experience with Chennai Trekking Club.

Kylie Adams:

And now, this is something I'm planning on doing for actually the rest of my life hopefully. Next year, I'll be up in Alaska working as an outdoor recreation therapist for kids with disabilities, taking kids near and around the Juneau area on skiing and hiking adventures. And, when I continue into a medical career in the future, that's something I want to focus on is, because I think that disability is not the actual physical impairment. I think it's the social and cultural environment that we have set up that makes people with physical impairments unable to participate on an equal basis with their peers, I think that's what disability is.

Kylie Adams:

I think that equalizing access to the outdoors and communities that value that is one of the best things we can do at keeping social integration and, therefore, health for people with disabilities. And that was something that, going into India, I didn't know I valued as much as I now realize. That growing up in Washington, right in the base of his beautiful volcano, Mount Rainier, and then going to India and having these experiences with the Chennai Trekking Club, and getting connected to Adventures Beyond Barriers, now is very much what I'm hoping to dedicate the rest of my career to.

Kylie Adams:

Almost everything I do, my India experience, in general, is something that's going to be taken forward with me, but especially all the relationships. For me, it's definitely about the people as much as the place. And so, several of the women that I had trekked with that were on this trek or that I had trekked with that weren't on this trek and all of us are now living with... we have the living memory of these people as we go forward. And just some of them were the most vibrant people that could laugh and make a joke out of the fact that we were sleeping under these tents during monsoon season or people lost shoes over cliffs. And just trying to bring even a fraction of that energy that some of these people I met had into my work with people with disabilities is something that I'm very aware of. And I think, even when I'm not consciously aware of it, I really think it's impossible to say that they didn't have that influence on me because they absolutely... it's somewhere deep down, at this point.

Chris Wurst:

I'm Christopher Wurst, director of the Collaboratory, an initiative within the U.S. State Department's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, or ECA. 22.33 is named for Title 22, Chapter 33 of the U.S. code, the statute that created ECA. Our stories come from participants of U.S. government funded international exchange program.

Chris Wurst:

In this episode, Kylie Adams shared a tragic, but ultimately uplifting, story from her time as a Fulbright researcher in India. The Fulbright Program operates in more than 160 countries, allowing its participants the opportunity to study, teach, conduct research, and exchange ideas in foreign countries. For more about ECA exchange programs, check out eca.state.gov. We also encourage you to subscribe to 22.33 wherever you find your podcasts. And we'd love to hear from you. Write to us at ecacollaboratory@state.gov. That's E-C-A, C-O-L-L-A-B-O-R-A-T-O-R-Y@state.gov.

Chris Wurst:

Special thanks this week to Kylie for her stories, and frankly, for her example. I did the interview with Kylie, along with Manny Pereira and Mary Kay Hazel, and edited this segment. The music you heard was "Coca" by Kiran Ahluwalia and "Peaceful Midnight Beauty" by Soft Mix. Music at the top of each episode is "Sebastian" by How the Night Came. And the end credit music is "Two Pianos" by Tagirljus. Until next time.

Season 02, Episode 50 - American Sister, American Sister - Abena Amoakuh

LISTEN HERE - Episode 50

DESCRIPTION

This week a Critical Language Scholarship (CLS) program participant from Atlanta, GA describes her experience while living in China and studying Mandarin.

Learning to better communicate boundaries, having your Americanness challenged, and cherry-picking with the neighborhood, join us on a journey around the globe through international exchange stories.

For more information about the CLS program visit https://www.clscholarship.org.

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Wurst:

You knew when you prepared to go to China, that the culture would be very different, but even then you were surprised at how much you stood out. Not only did people stare, they often wanted to touch you, and quickly you learned that the only way you could set your boundaries was to learn the local language just as fast as you could.

Chris Wurst:

You're listening to 22.33, a podcast of exchange stories.

Abena Amoakuh:

I think a lot of people in China thought we were really, really rich. Like, "Oh, you're here in China and you're studying here. You must have a lot of money." I think it's funny. We would always defend and say, "Oh, no, no. We're college students. We're still calling students, we don't have any money."

Chris Wurst:

This week, learning to better communicate boundaries, having your Americanness challenged, and cherry-picking with the neighborhood. Join us on our journey from Atlanta, Georgia, to China and learning to move beyond the stairs. It's 22.33.

Intro Clip:

(Music) We report what happens in the United States warts and all.

These exchanges shaped who I am.

When you get to know these people, they're not quite like you. You read about them, they are people very much like ourselves (Music)

Abena Amoakuh:

My name is Abena Amoakuh. Everyone calls me Abena. I am from Atlanta, Georgia, and I participated in the Critical Language Scholarship Program in the summer of 2016 in China, studying Mandarin.

Abena Amoakuh:

I kind of have a global background. Both my parents are immigrants from Ghana. So growing up, I did spend a lot of time getting to go back to Ghana because a lot of my extended family is still there. Between Ghana and the U.S., I'm very familiar. And so I got to college, I was looking for another language to study after studying Spanish for the entire time I was in elementary, middle, and high school. Not wanting to pursue Spanish again, I was like, "What makes sense?" And at the time I was studying business international management, so it made a lot of sense to study Mandarin with hopefully the opportunity to get to study abroad there one day.

Abena Amoakuh:

Through introduction to the language is really what introduced me to the culture and the history of China. I was actually very fascinated because I realized I didn't really know anything. You learn very minimal, or at least I learned very minimal things in school about China, but it's such a huge nation with such vast history and a lot to learn about it. I think it was especially intriguing because for so long, it was closed off from the world, but there were still so much going on there that I was interested in learning more about.

Abena Amoakuh:

I remember first getting there and everyone's staring at me and being fascinated with me and wanting to touch me. And I was like, "This is kind of weird. They watch TV here, they've seen black people for." I know for a fact that they like Michael Jackson and Beyonce, and they love basketball in China. But within those first couple of weeks, every day just got a little bit more and more uncomfortable. And at the time my language skills were not very good. So it was very uncomfortable and just overwhelming and not what I anticipated at all. It kind of stole the excitement a little bit away from it. And I think the biggest aspect of it was not being able to communicate how I felt about it or how I felt about people touching me or wanting to take a picture with me. I couldn't communicate in their language, so it was very, very hard.

Abena Amoakuh:

In the U.S. I grew up in Atlanta. Atlanta is a very black city, which was great for me. It was a great experience. Then going and Ghana, everybody looks like me. So to be in a place where I very, very much stuck out like a sore thumb was just very unexpected. I felt like I had to have a lot of patients, especially with the other people that I was with. They didn't understand the experience that I was going through. A lot of them were either white or they were Chinese American, so they weren't as uncomfortable as I was. And so trying to be patient and also be respectful of the culture, but also trying to get the same respect back was very hard. But I think eventually as I got better at speaking Chinese, I was able to communicate better and communicate my boundaries better.

Abena Amoakuh:

On the one instance, whenever Chinese people would approach me, they'd be like, "Oh, [foreign language 00:05:31]?" Is she African? And it's like, "Oh, yes. Yes, I am. But I'm American because I was raised in America. That threw them off. A lot of people don't know there are a lot of African students studying abroad in China. Nowadays it's not really a concept of black people being in China is foreign, I think it's still fascinating to a lot of people, especially older generations. So that was the one hand. I always identify very proudly as African American, quite literally both of those. But then also when I get to another country where they're challenging my Americanness, and I didn't know what to do with that.

Abena Amoakuh:

Challenging my Americanness because of my blackness. And it's kind of hard again to explain in a different language what that means. Because, for them, it was quite literally black and white. It was American or African, you can't really be both. What does that mean? Well, you look like this, so you have to be African and there's really not an in-between. I just had to understand that my identity was a little bit different in China and not not care, but also not let it get to me that it didn't change my personal identity or how I have already reconciled my own identity.

Abena Amoakuh:

At the time that I was there, it was the summer of 2016. So there's already a lot of speculation about the things that were going on in America. And so to not be in America when that was happening, I already felt very disconnected. But then as soon as people found out that you're American, they had all these questions about it and want to know so much more about it. I know what's going on, and yes I know the context of what's happening, but I can't really answer these questions that you're asking me because you're really challenging me in ways that I never thought about it. When you're no longer in a Western world and non-Westerners are asking you what's going on in your Western world, it's very hard to compose a straight answer or explain it in a way that makes sense.

Abena Amoakuh:

I think my Americanness was challenged a lot. In some ways I felt like I wanted to distance myself from my Americanness because it was just too stressful to handle at times. So sometimes I'd be like, "Yeah, I'm African. Yeah, I'm from Ghana." It was unique. I could kind of pick whatever identity I wanted to, if I really wanted to. I didn't do it often, but in uncomfortable situations I think I used it as a mechanism. Now I'm thinking about it, it's like, "Whoa, I actually was able to do that when I wanted to."

Abena Amoakuh:

There are a lot of Western things there. KFC, Pizza Hut, McDonald's. Those are three really popular restaurants there. Walmart is huge there. It's kind of amazing to see the way that these things are elevated in China versus the way they're downplayed in the United States. Going to Pizza Hut is a restaurant experience. You sit down and you get served and everything. KFC and McDonald's, same thing. Even movies and the way superhero movies are super popular. Those ideas of things and just like, "Oh, you're from American." The first question is like, "You know about this and this and this person. Obama and Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan." And all these artists and big people here who we're like, "Yeah, those are people we like too." And they're like, "We love them here." And they're like, "Have you ever heard of Jackie Chan?" And it's like, "Of course we've heard of Jackie Chan."

Abena Amoakuh:

But it's fun to talk about it with people because it brings some kind of common ground. So I think on one hand it could be annoying to people. It's like, "Okay, yes, you're naming all these American things." But for me it was exciting because it's like, "Great. You know about some things about American and maybe this can help us on a common ground or build a common foundation in some way."

Abena Amoakuh:

Well, once I got in a taxi and I was with my language partner, the taxi drivers started talking about me to my language partner. And this always happens. People are always talking about me in Chinese to the person who looks Chinese and thinking I don't understand them. And so I just interrupted in the conversation. I was like, "Oh, I understand what you're saying." And he's like, "Oh wow." And then he goes, "Obama. Do you know who Obama is?" I was like, "Of course I do." And he just got really excited and he was like, "I knew you were American." And I was like, "Oh really? Because everybody thinks that I'm African." He's like, "No, no, no, no. I could tell the difference. I've gotten to interact with so many different people, I can tell the difference now."

Abena Amoakuh:

I think I was eager to share especially from the aspect of them being very surprised that I was American. Being like, "Yes, America has all types of people." And if I was with a Chinese American person, it's like, "They're people like us. There are white people, there are native Americans. There there's all of that."

Abena Amoakuh:

There's things that are very obviously sacred in a sense. I lived with a host family and that was very interesting because I was very, very, very nervous about that. Considering I was going to be in somebody else's home, we didn't really know each other. One thing that was pretty cool to observe is how central the woman is in the family. In the sense that women handle the money and make a lot of the big decisions. So for my host mom, she worked full time, had two daughters, one was seven, one was five, and cooked every single meal for everyone. Which is very, very, very impressive to me.

Abena Amoakuh:

One thing I really liked about the culture also, it was the community aspect. So on one of the family outings, we went on people in the neighborhood, so they lived in a condo building and it was mixed with condos and some single-family homes as well. The housing association had planned a cherry-picking outing. So we went cherry-picking and literally there was five buses of families. It wasn't just mom, dad, kids, mom, dad, kids, grandfather, grandmother. The family unit is very, very strong and extended family living in one household is very strong. It's very beautiful to see. They're all friends and they all went on this outing together for the day. Some of my other friends in the program were also in some of the other host families, and they were all very keen to show us off and brag about us to one another like we were their own kids, which was really fun.

Abena Amoakuh:

The Chinese people have a lot of national pride, and there are some people who are very, very unsatisfied with the conditions and the type of government and leadership that they have to live under. There are a lot of things that are happening that was just very hard to see or hear about. That perspective is also very interesting, especially China is always in the news. And whenever I'm reading about it and reading about like, "Oh, wow, that makes sense." Or I saw underlyings or inklings of this happening, but now it's actually happening and things.

Abena Amoakuh:

I have a lot of friends who were still in China and experiencing that. Everybody's very unsure of what's going to happen and what it's going to look like. A lot of people keep on telling me, it's like, "Ooh, you know, Mandarin, that's going to be really, really good in the future." I'm like, "Well, I hope so. In a way that's beneficial, I hope. Not in a way that's detrimental to anyone."

Abena Amoakuh:

In China, you don't have access to a lot of things that you have access to, especially on the internet. So you don't have access to Google. No Facebook, Instagram. A lot of things are blocked. Things that we take for granted in a sense are very much blocked. Everybody has Gmail. All Americans have Gmail. And so you have what's called a virtual private network, a VPN. A lot of people don't know this, a VPN basically says, "Oh, I'm in Atlanta." Or, "Oh, I'm in Washington DC," but you're really in China, but it says you're using the internet from this other location. So we all use VPNs. They're very easy to come by. Most universities have them. So as university students, we all had one. And if not, they're pretty easy to purchase. They're like $10 for like a month.

Abena Amoakuh:

But a lot of the times it was very obvious that the VPNs were being disrupted, that the government or whoever was purposely trying to make sure that the VPNs weren't working so you wouldn't have access to those. And even now I still get the weirdest spam Chinese emails and I don't know where they came from. Stuff like that. There were times where we would heavy speculate, and we were like, "Did this happen to you last night?" "Okay, it happened to me too."

Abena Amoakuh:

I always used to joke of all the random pictures that gets taken of me without being asked and the videos that get taken to me, I was like, "I bet you I'm on all these websites. It doesn't even matter. The Chinese government knows who I am. They know my social security number at this point." I think we joked to make light of it, but it is actually a very serious thing that's happening. Making light of it was easier than thinking of what was actually happening. And also I definitely think it's a huge concern and actually is something very real that is happening.

Abena Amoakuh:

There were a lot of times where we would just like, "Okay, let's go on a weekend trip." Tho one weekend trip that we went to, I don't even know if I'm supposed to say this, but we went to Dandong which is the border at China City between North Korea and China. It's just a regular Chinese city, just much smaller. We were like, "Oh, yeah. This is going to be super easy. It's a super small town." Super small in China does not mean the same as super small in the United States of America. Because, let me tell you, super small is very, very big. So we were like, "Oh, the distance looks really short between the train station and where our hostel was supposed to be." Nope, 30-minute drive. Okay, so we had to take a taxi and there's eight of us. How are we going to make sure our two taxis stay together and they don't try to scam us. And our hustle just ended up being way out of the way.

Abena Amoakuh:

And we thought it was going to be a spa and things because we saw it on the internet. It was not that when we got there. There's really no food in the area. We got there so late that the kitchen had closed and so we're just walking on the street and all these people were staring at us and screaming at us and yelling and chasing after us. And we're just like, "LOL, this is so ridiculous. Really, can you imagine if our parents saw us? They'd be like, 'What the heck are you doing?'" A lot of the times I do this, I'll just be like, "I'm just going to tell my mom about it after it happens," because I don't want her to freak out if she knows it's happening right now. And so all of the stories I'd end up telling my mom after. She's like, "What? You did what? You hiked what mountain? You went where for what weekend?" I don't know, it was in Shanghai or Beijing.

Abena Amoakuh:

I don't know if my friends or family could really understand how different China is and really enjoy it as much as I did it. I knew I was just down for the adventure and the experience and it was a limited time, so why not try everything and do all these things that are outside of my comfort zone and that I wouldn't get to do when I got back here.

Abena Amoakuh:

I don't think I would have noticed it. The guide was just like, "That's North Korea." And I was like, "What?" At the time it wasn't as hostile environment, but the way Western news talks about it versus when you go there, it's so chill. Obviously it's changed in the last, what? It's been almost three years since I've been there, things have escalated. But at the time it was just so casual and all of us were just like looking at each other like, "Is this weird that we think this is weird that people are so casual about this?" Because we come from a society where everything is amplified. In the way it's talked about, it's very amplified. It really instills fear in you. And granted those two borders also do look very different, but still, I think we were just very much in awe. You can see into North Korea, which is crazy. I can say I've seen into North Korea and not many people can say that.

Abena Amoakuh:

One day I was going from home to class and my family lived on top of a hill that went down straight to the university, which was very convenient for me. I didn't have to take the bus or anything, I could just walk. It was the dead summer though, so it became very, very hot sometimes. Sometimes in the middle of the day when I was walking down to class, I would pass the preschool that my youngest host sister would go to. And so sometimes they'd be playing outside and she'd see me and scream across the street, "[foreign language 00:19:58]." Which is, "American sister, American sister."

Abena Amoakuh:

I remember, usually I passed on the other side of the street to avoid having to interact and her teacher being like, "Who the heck is this person?" But one day I just happened to be on the same side of the street at the school, and one of her little friends was like, "Oh, that's a black girl. That's your black sister." And she was like, "No, that's my American sister." She was so adamant about it, she's five years old, she's one of the sassiest people I've ever met. And I was just like, "Yeah, you tell them. You tell them." I loved that she didn't try to put me in a bubble or just be like, "Oh, the black girl is your sister," She's like, "No, she's my sister from America. And that's how we refer to her." And that made me feel really proud.

Abena Amoakuh:

It's not something that I taught her or anything like that, it's just her naivete and her just being a young person. And her not seeing me in a certain way was really exciting and I was proud of her for that because at that point I didn't really know if she liked me or not.

Abena Amoakuh:

In the evenings, a lot of the grandmas and the grandpas, they get into the square or something commune spot and they do Tai Chi, which is just very fun to watch because they're very dedicated to doing that. Morning markets and kind of fresh food in the market, every time all of us would walk down to school, if we didn't get breakfast at home, we would get it off the street. It's super easy and convenient and very, very normal to do that. Starbucks is not a morning breakfast thing. That's an afternoon delicacy delight thing. Oh my goodness, I can think of the afternoon and leaving class and there being so many people in the street and so many buses. Buses there are stick-shift and they're very terrifying because they're barreling towards you and all cars have the right of the way.

Abena Amoakuh:

So I can just hear the honking and the pitter-patter of shoes running quickly across the street. And all the motorcycles are super loud and smell the exhaust, see the pollution. Restaurants are always super loud. People really gather and like to gather around food, and so restaurants are always super loud and super crowded. Service is not a thing in China, you yell for your waiter. So [foreign language 00:22:23]. You yell for them, you yell for your check, you yell for anything that you want. So they're a loud and lively place, but people are obviously very happy there and enjoying themselves.

Abena Amoakuh:

But there's always a way to find fun in good situations. Yes, they're going to be bad experiences or things that are like, "I never want to do that again." Or, "Maybe I don't want to come to this place again." But for me, I am anticipating and I'm super excited for an opportunity to go back just because I've seen parts of China, but I have not seen so many parts of China. And I think I have a unique advantage in understanding the language and being able to speak some of the language. Even while I'm still here and reading about things that are happening in China or learning new things, I'm just like, "Wow, that's so cool. Why didn't I do that?" Or sometimes my friends send me things about travel stuff in China and they're like, "Have you been to this place? Or have you heard of this place?" I'm like, "No, I haven't even heard or seen of this."

Chris Wurst:

22.33 is produced the Collaboratory, an initiative within the U.S. State department's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, better known as ECA. My name's Christopher Wurst, I'm the director of the Collaboratory. 22.33 is named for Title 22, Chapter 33 of the U.S. Code, the statute that created ECA. And our stories come from participants of U.S. government-funded international exchange programs.

Chris Wurst:

This week, Abena Amoakuh discussed her time in China as a participant in the Critical Languages Scholarship, or CLS Program. For more about CLS and other ECA exchange programs, check out eca.state.gov. We also encourage you to subscribe to 22.33. You can do that wherever you find your podcasts. And we'd love to hear from you. You can write to us anytime at ecacollaboratory@state.gov. That's E-C-A-C-O-L-L-A-B-O-R-A-T-O-R-Y@state.gov. Photos of each week's interviewee and complete episode transcripts can be found at our webpage at eca.state.gov/22.33.

Chris Wurst:

Special thanks to Abena for her willingness to share her stories. I did the interview and edited this segment. Featured music was Mr. Mollinson. One Needle, Picnic March, The Poplar Grove, and Plum King, all by Blue Dot Sessions. And Preludio 1976 by Himalayha. Music at the top of each episode is Sebastian by How the Night Came. And the end credit music is Two Pianos by Tagirljus. Until next time.

Season 02, Episode 49 - Don't Worry Mom, It's Just the Arab Spring - Kristen Erthum

LISTEN HERE: Episode 49

DESCRIPTION

It's Arab Spring, political upheavals are occurring throughout the Middle East spill out into the streets and not only are you suddenly living in the midst of it all, it just so happens that your grandmother from Nebraska is visiting. And while everything might feel light years from life in the American Midwest, what strikes you most in the end is how similar we all are. You're listening to 2233, a podcast of exchange stories.

TRANSCRIPT

Kristen Erthum:

Three plus seven is ten, as is eight plus two, as is five plus five, and how you get to the answer sometimes doesn't matter. I think that the way that things change you, that travel changes you, is you're less afraid of the unknown. You are more hyper skeptical of things. You question it. You question what you see. People say, "Well, the sky is green." And if where you live, the sky is green, that's all you've ever seen, then you believe the sky to be green. But if when you travel and you see that the sky is blue, or the sky is white, or the sky is gray, you're like, "Wait a minute."

Chris Wurst:

This week: Getting one's shop on in the Egyptian markets, a first glimmer of a freer future, and learning to love the gray areas. On this episode, a journey from the cornfields of Nebraska to Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, and embracing our differences.

Intro Segment:

(Music) We operate under a presidential mandate, which says that we report what happens in the United States warts and all.

These exchanges shaped who I am.

And when you get to know these people, they're not quite like you. You read about them. They are people very much like ourselves. And it was possible to create a-

(Singing) That's what we call cultural exchange.

Kristen Erthum:

My name is Kristen Arthum. I am originally from Ainsworth, Nebraska. I now live in the DC area. I am a Fulbright 2010 ETA from Egypt. I'm one of the only 10 to my knowledge that you will ever meet, so we are a rare breed.

Kristen Erthum:

The world changed on 9/11. I was 13. And what I remember the most, besides what you see on TV and the horrific stories that we tell, is that there were no airplanes flying over. We're a fly over state. We had no airplanes flying over for three days and the world literally changed. 9/11 is now a historical event for most people in school, but for us, that was a big thing. And so you saw this wave of ugliness that followed afterwards. About people who were different than we were, that looked different, that might pray different, that had different backgrounds. And it really got me interested in, let's see what the world is like. Let's see what this is.

Kristen Erthum:

I have a traditional American background. My family comes from all over. We came in times of great strife and part of my family happens to be Syrian and so knowing that we were Arab, I wanted to know what that was.

Kristen Erthum:

Lo and behold, I got my Fulbright and it was one of the most amazing things that I think ever happened to me. Starting out, you take a kid from the Midwest who has really only ever been to one country, and that was Jordan. You throw them into Cairo, which is a city. They say it's 20 million, it's more like 33 million people. It's loud, it's busy. There's people everywhere. Sanitation isn't what you think it's going to be, so there's pile of rotting food scraps in the street. There's dogs, there's cats, there's women, there's children, there's cars. Egyptians talk with their horns, so you have, "Hey, good to see ya neighbor." Beep beep. You have, "Get out of my way." Beep beep. You have, "I'm going to run you over." Honk, honk, honk. It's just different from the Midwest.

Kristen Erthum:

Big change and just that culture shock of, "I'm not going to be able to make it here." And there's times that you're sitting there eating whatever quintessential Egyptian food it is. If it's mushy, which is cabbage or zucchini stuffed with rice. Or it's koshery or it's [Arabic], which is beans. "I'm not going to be able to do this." Then you get thrown into your site and for us, my site was in Ismailia. It's the city that controls the Suez. And so you feel the ships that have the sound that's so low that it just literally vibrates your insides going through the canal.

Kristen Erthum:

And we were teaching at a [Arabic] Canal Suez and they threw us into a classroom with 300 students and said, "Teach them something. Teach them whatever you want. There is no curriculum. There is no real thing that we want them to learn. We want them to learn English." And so what I did was I had my students write, "What is your greatest fear? What do you want to be when you grow up? Are you a cat or a dog person?" Just to see what they needed.

Kristen Erthum:

I think the one thing being 22, 23 on a Fulbright that I learned, is who you are when nobody's watching and how you respond to things that are different. I know people that completely shut down and curl up in themselves and these are the people you're going to meet on Fulbright. But the people that blossom and say, "This is who I am. And this is how I represent myself." Is key because you don't travel and come back the same. You come back different. And the ways that you're different, you won't know until they start to manifest. And that's the cool part of it.

Kristen Erthum:

In January of 2011, in Tunisia, which is basically a neighbor of Egypt minus a few countries, there was a guy that set himself on fire to protest the price of bread and for very complex reasons that academics know, that started what is known as Arab Spring. And we were there for Arab Spring and we saw, I remember having this conversation with Megan, my site mate, about when Ben Ali fell in Tunisia, the ability of Egypt to go through that revolution. We said, "That's never going to happen here." The moment you say something's never going to happen, guess what's going to happen? The truth is stranger than fiction sometimes. And it did happen.

Kristen Erthum:

January 26th. My grandmother was visiting from the U.S. My grandmother, love her, is more adventurous than I am and had this whole list of countries that ended with her coming back to Egypt. So, I met her in Cairo.

Kristen Erthum:

We were in Khan el-Khalili which is the big market down by [Arabic 00:07:48] mosque. It's got that what you would think to be the quintessential old world market feel. There's kit shops with stuff that's obviously meant for tourists on these narrow winding streets. There's also an Egyptian side. So I told grandma, I said, "I'll bust you out of your tour because our guy's tours can be really boring and I'll take you to Khan el-Khalili and we'll do the shopping and we'll negotiate like Egyptians do."

Kristen Erthum:

So, we show up at Khan el-Khalili and it's 8:30 in the morning. The market should be full. It is not. And I'm like, "Hey, more shopping for us. Let's do this." So, we get our shop on. We buy a whole bunch of stuff for not a whole lot of money. And then I'm like, "Let's go do some other things."

Kristen Erthum:

And so we tour around the lesser known parts of Cairo and enjoy the lesser known parts of Cairo and I make this joke that's like, "Let's go to Tahrir Square," What is ground central of the Egyptian revolution, "And get some ice cream?" And she goes, "No, no, I don't want ice cream."

Kristen Erthum:

So, we go back to her hotel and we turn on the TV and there's these pictures of Tahrir Square. Attacker your square. I don't think anybody understood the magnitude of what we were going to be dealing with. And so my grandmother left the next day. I was flying to Sydney via Abu Dhabi and I thought that my taxi cab driver was taking me on a route that was really circuitous. We went up all the way around the city, instead of going through the center of the city. I get to Abu Dhabi, turn the news on again, it's getting worse. And I remember thinking to myself, "Egypt, you better settle down because I'm coming back in 10 days and I expect you to be here when I get back."

Kristen Erthum:

And I think it's three days, four days into my stint in Sydney and I get this call at 3:00 AM and it's the director of the Institute. He goes, "Well, things have gotten bad enough here in Egypt that for the safety of the program, we're evacuating everybody. Whatever you do, don't come back until we say so."

Kristen Erthum:

Once Egypt settled down, they said, "Well, come on back." So, I came back in April and they said, "We're putting you back where you were and continue what you were doing." But what was different about coming back for me was you had a country that for the first time, the best way to describe it was tasting democracy and tasting freedom.

Kristen Erthum:

And so I taught the classes that I was supposed to teach, which was an English writing class. Like how to write a five paragraph essay, vocabulary, speaking. But I also was in charge of language lab. So was able to have these conversations about what is democracy, what is citizen responsibility, and what are fundamental freedoms, fundamental rights, and really tried to get the students to focus on this is a pivotal moment in your history. How do you want to shape your country and more importantly, how are you going to be the first generation to add to that? What is your legacy?

Kristen Erthum:

And really focused on their hopes and dreams and fears of what was coming and it was really exciting for me to see these things and to understand, this is what it must be the first time you taste it.

Kristen Erthum:

It was difficult. There's difficult parts of it. I was in Egypt when Osama bin Laden was killed and the first that was that very American, "Hey, we got the guy that hurt us." The second thought I had was, "And I'm living in the middle East. What do I do? Do I go to work today?" You're hyper aware of things around you because you are different and that difference is sometimes celebrated and sometimes not appreciated and so learning to navigate that and find commonalities with people is something that the exchange programs teach.

Kristen Erthum:

I went to an orphanage because one of my friends randomly knocked on my door at 6:30 in the morning on a Saturday. So, I show up to this orphanage where my English ... My English is fine, but my Arabic is not great. And we're dropping off the stuff, we're giving toys to the kids. I learned how to say [Arabic 00:13:14] which basically means, "Maybe I can open it for you." But these kids were running around with these oranges that we had bought them because they don't have access to fresh fruit and didn't know what to do with them. And so you've got these four year olds running around, they think I'm taking their orange from them at this point and I'm going to keep it. And I'm like, "No, no." So, I walked to my friend. I'm like, "How do I say, can I peal that for you?"

Kristen Erthum:

And they said, [Arabic 00:00:13:36]. I'm like, "Okay, [Arabic 00:13:39]" and point to the orange. And so the kids give it to me and then they realize I'm going to peal their orange. I probably peeled 40 oranges that day. They were just all running up to me and be like, "Peel my orange for me!"

Kristen Erthum:

We brought joy to those children's lives, even if for only that afternoon. And I smelled like oranges for three days because it just was ... I watched so much, it just wasn't coming off. Not a bad smell. I've had worse.

Kristen Erthum:

We all want the same thing and that's to be happy, to feel at peace, to feel like we're not constantly searching for the next meal or dollar or whatever it is. And just to have meaning in this life. And you realize that when you're abroad is that we do things differently, but we all want the same thing at the end of the day. And that's to feel like that we've contributed, that we belong and that we have a place in this world.

Kristen Erthum:

And what that means changes from culture, but it's true. That's what we all want. And it's fun. There's fun. Parts of it. There's definitely growth parts. Being from the Midwest where I went to church every day and then meeting people that happen to go to mosques and comparing the cultures and the religions and the way that culture layers onto religion is really interesting.

Kristen Erthum:

I had a chance to ask questions about Islam that I really hadn't felt comfortable asking anybody else. They also did the same thing about Christianity to me. It makes you know your own faith a little bit better because, "They'll ask you, why do you do it this way?" And honestly, the answer is sometimes, "Because."

Kristen Erthum:

"Well, what do you mean because?"

Kristen Erthum:

"Because that's the way I learned it. There's a different way to do things."

Kristen Erthum:

And that was cool because you confront your assumptions. That's another way it changes you, is you confront your assumptions about the world and realize that everything is not black and white, it's really shades of gray. And that's awesome.

Chris Wurst:

I'm Christopher Wurst, director of the Collaboratory, an initiative within the U.S. State Department's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, or ECA. 2233 is named for Title 22, Chapter 33 of the U.S. Code, the statute that created ECA and our stories come from participants of U.S. government funded international exchange programs.

Chris Wurst:

In this episode, Kristen Arthum shared her unique experiences as part of ECA's Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Program, which sends Americans abroad to assist classroom English teaching and as in Kristen's case, is usually just as educational for the teachers as for the students. For more about ECA exchange programs, check out eca.state.gov.

Chris Wurst:

We encourage you to subscribe to 2233 wherever you find your podcasts and we'd love to hear from you. Write to us at ecacollaboratory@state.gov. That's E-C-A-C-O-L-L-A-B-O-R-A-T-O-R-Y @state.gov.

Chris Wurst:

Special thanks this week to Kristen Arthum for sharing her insights. I did the interview with her and I edited this episode. Featured music during the segment, "Them Dirty Blues" by Cannonball Adderley. "Everything's Moving Too Fast" by Peggy Lee with Dave Barber and His Orchestra, and "Night Owl" by Broke For Free. At the top of the show, you heard "Sebastian" by How the Night Came and to play us out, "Two Pianos" by Tagirljus. Until next time.

Season 02, Episode 48- The Tricked Out Rickshaw - Patty Esch

EPISODE 48 - Listen here

DESCRIPTION

This week, hear about the sweetest rickshaw ride in Mumbai, the funniest man in India, and what it's liked to be dragged onto a Bollywood dance floor. Join us on a journey from Colorado to India, to learn that sometimes it just easier to be your real self. This is 22.33, a podcast of exchange stories.

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Wurst:

You're living far, far away, let's say in India. And you're constantly aware of everything that you do or say because you are terrified of offending the local people. It takes a lot of energy. Until the moment when you realize that not only is it easier just to be yourself, it also makes you much more authentic as a cultural ambassador. Your biggest lesson, just be.

Chris Wurst:

You're listening to 22.33, a podcast of exchange stories. This week, the sweetest rickshaw ride in Mumbai, the funniest man in India, and being dragged onto the dance floor. Join us on a journey from Colorado to India, to learn that it just takes less energy to be real. It's 22.33.

Intro Segment:

(Music)

We report what happens in the United States warts and all.

These exchanges shaped who I am.

And when you get to know these people, they're not quite like you read about them. They are people very much like ourselves, and...

(Singing)

Patty Esch:

In Mumbai, I had this rickshaw driver who picked me up one day after I had gone to this... Random, but this meditation session. And it was just like a really awesome experience. But then I got in his workshop and it's decked out. It is decked out in all these posters, pictures, everything. And he's got like hand sanitizer and he's got chive for 5 cents in his rickshaw, like he has everything. He's wifi onboard everything.

Patty Esch:

And so, this man is like, "Hey, how's it going? Where are you going to?" We tell him, and then we start looking around and I realized that it says, "50% of proceeds go to cancer patients." And I was like, what? This man probably makes very little throughout the month being a rickshaw driver, but he donates 50% to cancer. I don't believe it. I was very skeptical at first.

Patty Esch:

We start talking to him more and in the rickshaw, I'm looking up videos of him, of his interviews with CNN and all these places. And just talking to him, you can just get like such a general feel of a person. And he was the most giving, caring and hilarious, man I met in India.

Patty Esch:

My name is Patty, Patty Esch. I'm from Colorado. I went to school in Arizona. I did my Fulbright in 2017 to 2018. I'm a student researcher. I studied liver cancer and how genetic predisposition to liver cancer is distributed or affects populations in India differently. And I was in Mumbai for my research. I spent three months in Poona doing language studies. I studied Marathi and then I spent six months in Mumbai.

Patty Esch:

And I decided that that wasn't enough of an interaction for me. I asked him if I could invite him over for lunch or whatever could happen. And he said, "No, no, no, of course not. You can come to my house. You should come to my house and meet my wife, and my daughter and my son won't be there because he's in school. But I would love for you to come and meet my family." And I really forced the issue. I was like, "No, no, no, I'm going to meet these people. I'm going to like hang out with you more." He invited us over to his house. It was my friend and I, and he invited us over to his house.

Patty Esch:

And I lived in a pretty ex-pat heavy part of Mumbai, Bandra is the location. And he lived just on the outskirts of Bandra, a place that I had never been, never even knew existed. And we met him there and his family hosted us for this amazing dinner. And we talked about everything. We sat there for hours, so many hours that my friend and I had had plans to meet up that night. And she texted me and I didn't see my phone, and she was freaking out because she knew that I was going to this random rickshaw driver's house for dinner, and she thought that I had gotten kidnapped or something.

Patty Esch:

I just remember sitting on the floor and they're tiny, tiny apartment. That's painted this beautiful, brilliant green color. And they decide to paint it a different color every year. And the wife had gotten home from work. She works with helping women get access to grants and understanding government schemes. Like she does this amazing work. She came home early to cook dinner and made this amazing dinner for us, that was something I've never had before. And I had lived in Maharashtra for like nine months at this time, eight months.

Patty Esch:

And we sat on the floor, sharing dinner, sharing stories. My friend spoke Marathi and Hindi. And so, we were able to translate pretty well between all of us. And it was just like the most amazing experience. We learned a lot from them. We tried to give him some like business advice because he deserves so much for what he does. But I think just, I realized that like food is such a connection for people. To sit together, share a meal over a couple of hours of time and learn about each other.

Patty Esch:

My partner came from the U.S. to visit and we got invited to his coworkers wedding. His coworker was getting married in Chennai. We got to go to this wedding and we're at the first day... Or no, the third day, I guess, of the wedding and it's the groom's procession, so he rides up on this horse, super magical. And he's going up to greet the bride and the bride's family. And all of his family and his friends are dancing around him. It's Chennai, so it's hot, sweaty. My leg hurts and I'm like, "Oh, no way am I dancing." People pull my partner into the crowd and they're like, "Oh, you have to dance. You have to dance." It's mostly men at this point, so I'm kind of just standing in the background.

Patty Esch:

But one of my favorite memories is this elderly couple who were probably in there like eighties, they spot me, because I'm like a neon sign at this wedding, the only foreigner there. And they spot me and they drag me onto the dance floor into the procession. And they're just dancing with such vigor and such youth more than I've ever seen anyone dance with. And it was just like they're making sure that everyone is dancing, that everyone is included in this moment. And it was just a really awesome opportunity to just let loose and to not be such a foreigner, like no one cared what you were doing, the way you're moving. It's just sharing the space and sharing the energy and feeling the music, and it was such a happy experience. I forgot about everything else. I had all these reservations about like, "Oh, I don't want to dance. I don't want to dance wrong. I don't want to dance because my leg hurts." It was all these things. I think in the end, this taught me a greater lesson.

Patty Esch:

Throughout my Fulbright experience was that it takes less energy to just be real. Like it takes less energy to just be who you are and whatever excuses you want to come up with, to not do something, they're not as good as the experience you'll have when you do decide to do something, It's easy to get caught up in the "Oh, but I shouldn't, or I should" To just be, just be who you are. And that was one of the best things that I learned.

Patty Esch:

As a cultural ambassador, you go into a place not doing as much research as you can, right. Reading as many books, talking to as many people. But I think the best way to be a cultural ambassador is to be yourself. I stopped saying like key phrases, key West Coast phrases that I have, because I was like, "Oh, people might not understand what I'm saying. Like they might not understand my specific dialect." And I tried to say things a certain way. And I think you, to a certain level, you have to do that, and you kind of adapt to that, but you're there to share your culture while you take some. When I realized that when I wasn't being comfortable in who I was, and I was trying to be this perfect American representation, I wasn't being enough of an American representation, because I was just trying to be this like reflective mirror to them.

Patty Esch:

And so, after I realized that I was kind of holding back and being who I was, I needed to let go. And at that moment I became more of a cultural ambassador than I think I would've ever been, because I started saying things like "For sure," or showing people my favorite TV shows and dragging people to movies with me, or sharing really good books that might not have the most context in India, but just sharing these small moments of who I am, was really important.

Chris Wurst:

22.33 is produced by the Collaboratory, an initiative within the U.S. State department's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, better known as ECA. My name's Christopher Wurst, I'm the director of the Collaboratory. 22.33 is named for Title 22, Chapter 33, of the U.S. Code, the statute that created ECA. And our stories come from participants of U.S. Government funded international exchange programs.

Chris Wurst:

In this episode, Patty Esch told us about her Fulbright experiences in India. For more about ECA exchanges, including the Fulbright program, check out eca.state.gov. We also encourage you to subscribe to 22.33. You can do that wherever you find your podcasts. And of course, we would love to hear from you, and you can write to us anytime. Write early, write often to ECAcollaboratory@state.gov, that's E-C-A-C-O-L-L-A-B-O-R-A-T-O-R-Y@state.gov

Chris Wurst:

Special thanks this week to Patty for taking us aboard the coolest rickshaw on the planet. I did the interview with her and also edited this episode. Featured music during the segment was Haratanaya Sree, Veena Kinhal. Music at the top of each episode is Sebastian, by How The Night Came, and the end credit music is Two Pianos, by Tagirlius. Until next time.

Season 02, Episode 47 - Everyone Can be Good at Math - Allie Surina

EPISODE 47: Listen here

DESCRIPTION

In this week's episode, a Fulbrighter from Western Kentucky University travels all the way to Shiyan, China to study math teacher education and discovers that both math and American sitcoms are truly universal languages.

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Wurst:

You traveled to China to study how they prepare people to teach math. You knew you'd stand out as a foreigner, but you didn't expect that language limitations would reveal just how you felt about yourself and what it means to be an American. You're listening to 22.33, a podcast of exchange stories.

Allie Serena:

There's many ways to feel foreign in China. I mean, I have bright blonde hair, my skin tone is different, I'm much taller than the average woman. Although I'm just a very typical pear shaped American woman. For a Chinese woman I represent this gross destruction of thighs. I mean just constantly, wherever I walked people would stop me and tell me, "Wow, your legs are so big." And they would say it to each other, "Her legs are so big," thinking I couldn't understand them. So everywhere I went, if I was walking down the street, a worker might be out smoking out of the window on his break and he'd see me and he'd get up and flail his hands out the window and say, "Oh, foreigner, foreigner, foreigner," and everyone would come out and look out the window.

I lived in a place where there weren't any foreigners so I was a daily spectacle and there were so many moments when I just thought, "There's nowhere I can go that I'm not the most obvious person and that everyone doesn't wonder, what is she doing here? Why is she here? What is she?"

Chris Wurst:

This week, learning that everyone can be good at math. Bonding over the Gettysburg address in Chinese, and a reminder that anybody can be somebody in America. Join us on a journey from Kentucky to China to discover that math and American sitcoms are truly universal languages. It's 22.33.

Speaker 3: We report what happens in the United States, warts and all

Speaker 4: These exchanges shaped who I am.

Speaker 3: When you get to know these people, they're not quite like you. You read about them. They are people very much like ourselves and...

Allie Serena:

My name is Allie Serena. I am from the West coast originally, but I was living in Kentucky going to Western Kentucky University when I applied for a Fulbright and I went to Shiyan, China to study math education and math teacher preparation.

Growing up, I was always very excited about math. It was a strength of mine and I was in a California school that had a peer tutoring program where you were able to tutor people in grades below you. And I tutored math to younger students, and I did that all the way through school. And then when I was out of high school, I did it at a community college and I was meeting people that were from all walks of life, whose life stories were incredibly difficult and who were coming back to school and coming back to, often remedial math to make a big change in their life. They wanted a second chance and math was the key for them. So I learned through math education about the ups and downs of American life and how it can be a door through which people can have access to really great opportunities. Or for others, it can be a ceiling beyond which they just don't feel that they can ever get past and so always loved math.

When I was in Western Kentucky University, I was studying economics and math and I was watching China grow on our radar as this huge economic development story. I was amazed by it, but also I was in wonder that they were able to lift so many people out of poverty and into educational attainment, especially with high degrees in engineering and math heavy subjects. For Americans it's very difficult to ever get better at math. We have this small percentage of people that are just naturally good at math, and then everybody else dreads math class and dreads math tests, and would never want to take a math major if they could avoid it. So how was China able to go from poverty into this factory pumping out math degrees and engineering degrees? So I was very interested in the role of math in promoting education in society and developing job readiness and economic development, and specifically in Chinese economic prosperity.

So when I went there, I was in a cognitive science laboratory where people are learning about how people learn and how people retain information. So I had that perspective of, we're looking at math in the, in terms of how people process information and how teachers can aid in that. And then I was also meeting with teacher groups and learning from the teachers themselves how they prepare. And so one very important difference is when a teacher is going to be a math teacher in China, they study at a university, four year university that is a teacher's college and they study to become a teacher. So everything they're learning, they're learning as a future teacher. When they're going to be a math teacher, that's the only subject they're going to teach. So they have half their day where they'll teach math and the other half is just preparation time for them to get better at teaching math, for them to look in on other colleagues work, to see how they teach to learn from the best of the best.

And so there is a lot of time and energy preparation that goes into each teacher to make sure that they are really, really good at teaching math. And we don't have that here. We have teachers who are in elementary school, teaching every subject. They may have 40 minutes for preparation, and that's being consistently carved down to smaller amounts of time. To be able to look back critically at your performance in teaching math. I mean, when did they get to have that? So I definitely saw from the very beginning that teacher preparation is so different from American teacher preparation and the results really speak for themselves. The teachers are confident in the subject. They're thinking about different ways to teach different concepts so that every student in the room can understand it and process it. And then the students themselves are taught about what math is in a very different way than we are.

We here think, well, math is something that you're just good at innately. Some are and then some just struggle to get through, to be at some medium level, you just want to do pain management. In China, math, like a lot of things is just something that you have to practice to get good at and anybody can be at a high level of math and can be expected to get a hundred percent on all of the tests leading up to some PhD level at which the real unique creative thinkers start to emerge and go off in their direction. But math as a concept and as a subject is something that everybody can be great at. And that's just the expectation. It's essential to life. You're naturally going to be very good at it if you practice. There's nobody, except for a developmental disabilities, would struggle with it. There's no reason to cry about it. Maybe it's not as fun as drawing, but it's certainly not something that you should think that you're going to be bad at.